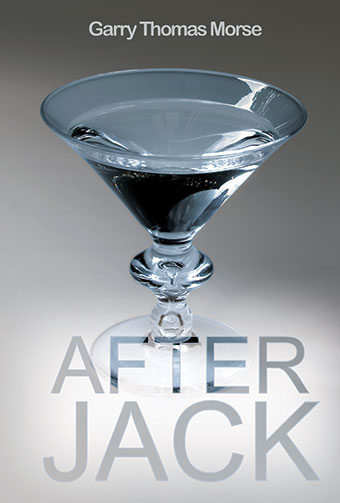

Paperback / softback

ISBN:

9780889226074

Pages: 320

Pub. Date:

June 1 2009

Dimensions: 8.5" x 5.5" x 0.75"

Rights: Available: WORLD

Categories

Fiction / FIC019000

- FICTION / Literary

Shop local bookstores

Garry Thomas Morse deploys his prodigious classical repertoire to compose the edgy new voices that reflect the cultural simultaneity of our everyday—a transnational, ahistoric cosmopolitanism: an idealized Helen is confounded by Molly Bloom’s monologue from Joyce’s Ulysses; a Dostoyevskian character parodies the libidinal excesses of William Burroughs with “the stone that drives men mad” from Pauline Johnson’s Tales of Stanley Park; an incident from The Book of Judges answers one of Gogol’s riddles; an acidic response to the recent fascination with “speculative fiction” introduces a punch card system from the year 2088 in which future language facilitates only business transactions in a completely monetized world; and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s alcoholism hits rock bottom in the unfulfilled desires of a dry pub crawl.

All of these stories seem to sketch the details of immediately recognizable places, but reveal a luminous interiority we never dreamed might be (re)discovered there. Transparently rooted in the work of other authors, including Garry Thomas Morse’s contemporaries, they nevertheless defy critical terms such as “intertextuality” and “authenticity.” Since his mother’s people (the Kwakwaka’wakw) became disconnected from their traditions there has been a great deal of forgetfulness of the “dream-time” that used to exist in our everyday lives—this forgotten “theatrical madness” of the human condition is what Morse seeks to re-present.

The title story of this brilliant collection of avant-garde fiction, loosely based on The Picture of Dorian Gray, Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, and the film Death in Venice inverts the post-modern textual convention that only the author’s voice can be considered authentic. Its main character—the artist Padam, who is no more “fictional” than the author—constantly interrogates the accuracy of his representations, whereas we know almost nothing about the narrator, who exists merely as the “subject” of the Padam’s portrait and an “object” of his reflection.

“Admirers of James Joyce, Malcolm Lowry, and Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice will be intrigued by Garry Thomas Morse’s strong collection of stories entitled Death in Vancouver. Though often exhibiting echoes of the great masters, these stories are certainly new, anchored solidly in the author’s West Coast world. In the title story, especially, the author has built an original tale vibrating with strong reverberations of the Mann novella and making use of locations that found their way into Lowry’s writing. Despite its roots in giant works of the past century it reads as authentically new, thanks in part to that obviously contemporary narrating ‘street voice’ — combined with subtle First Nations references. It is a reminder that we all live in a world that has been created by those who came before us and who are, in some way, still with us.”

— Jack Hodgins

“Garry Thomas Morse is an extraordinarily talented writer, and his Death in Vancouver is nothing less than a stunning accomplishment. It is work of prodigious erudition and imaginative daring, and it brings vividly to life (and death) the entangled narratives and sonantic richness of the global city.”

— David Chariandy

“Death in Vancouver, a selection of short prose bits with crazy compelling characters, tight, precise and breathtaking language and imagery and opera! I am enthralled by its originality. His writing reminds me of John Lavery’s work; they both are adept at linguistic “acrobatics” and are skilled in painting memorable and unusual characters.”

— Amanda Earl

“In Death in Vancouver, the story ‘Salt Chip Boy’ is very fine and intriguing, with the severe Baudrillard disconnect between mind and body, the cyber push in the direction of William Gibson and beyond, the cheeky use of ‘K’ which holds a whiff of Kafka, and the language which makes one feel as if they’ve stumbled (with satisfaction) into times far hence.”

— M.A.C. Farrant